FILM: ‘FALASHA’ SHOWS ETHIOPIAN JEWS’ PLIGHT

Only 25 years ago, few knew that there was a black Jewish community in Ethiopia. Today, anyone walking through the streets of Israel sees black Jews from Ethiopia who all now live in Israel. The recently deceased Israeli Prime Minister Yitzchak Shamir was a key player in Israel in deciding to bring this Jewish community from Ethiopia to Israel 20+ years ago. But how did this lost community of Jews receive the exposure necessary to be brought home to Israel by the Israeli government? Some say that the documentary film Falasha, by Simcha Jacobovici, had a part to play in creating the awareness for this Jewish community.

Ethiopian Jews in Israel today

Here is an article in the NY Times from 1985, a year after the film Falasha was completed:

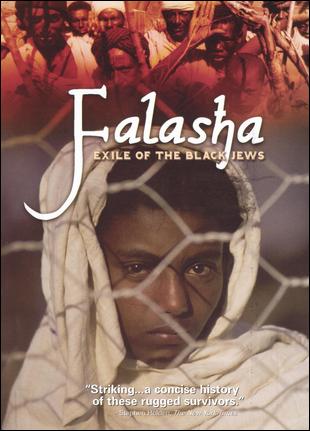

SIMCHA JACOBOVICI’S documentary film, ”Falasha: Exile of the Black Jews of Ethiopia,” is a quietly anguished examination of a 2,000-year- old culture facing extinction. The title, which means ”Stranger” in Amharic, is the word with which some Ethiopians label their Jewish compatriots. It is considered derogatory by the Jews, who refer to themselves as Beta Israel, or House of Israel. Ethiopia’s Jewish community, which according to legend descends from Solomon and Sheba, has remained intact during centuries of anti-Semitism, despite its isolation. Today it numbers about 25,000.

SIMCHA JACOBOVICI’S documentary film, ”Falasha: Exile of the Black Jews of Ethiopia,” is a quietly anguished examination of a 2,000-year- old culture facing extinction. The title, which means ”Stranger” in Amharic, is the word with which some Ethiopians label their Jewish compatriots. It is considered derogatory by the Jews, who refer to themselves as Beta Israel, or House of Israel. Ethiopia’s Jewish community, which according to legend descends from Solomon and Sheba, has remained intact during centuries of anti-Semitism, despite its isolation. Today it numbers about 25,000.

The film, which was completed last year and opens today at Film Forum 2, tells a story that continues to make front-page news. Facing persecution in addition to famine within Ethiopia, about half of the country’s Jews have escaped to squalid refugee camps across the Sudanese border, where they wait for the opportunity to immigrate to Israel. In these overcrowded camps, the Jews remain a shunned and viciously abused minority. Secret airlifts by Israel relocated about 10,000 Ethiopian Jews after the exodus began, but when the press broke the story, the operation was suspended. Meanwhile, 2,000 Ethiopian Jews have died in the camps while awaiting rescue, and another 2,000 remain stranded.

Simcha Jacobovici, an Israeli-born film maker, journalist and political scientist based in Toronto, has reported extensively on the situation. His film presents a concise history of these rugged survivors, and a survey of the political pressures in Israel and elsewhere that may have impeded rescue operations. Among the delicate matters taken up are Israel’s dependence on Sudanese good will because of geography, and the possibility that racism is behind Israel’s reluctance to address the crisis more decisively. As one commentator puts it, ”The Falasha is Jewish, black, Zionist, and third world all in one, and such a person doesn’t win friends.”

On the other side, the film gives ample evidence that the Ethiopian Jews who have made it to Israel have been assimilated with remarkable ease – so smoothly, in fact, that their distinctive African culture is in danger of eradication.

192.168.1.1 is the default IP Address of Wireless Router & ADSL Modem. Get 192.168.l.l ip addresslogin & password, wireless router settings & configuration steps free

The most striking moments in the film, most of which is devoted to conflicting political speculation, are scenes shot on location in Ethiopia and the Sudan. In a remote mountain village of Ethiopia’s Gondar province, we are shown a community of Ethiopian Jews barely eking out a living from the land, and are told of oppression and torture at the hands of local peasants’ associations. Out of sight of an official guide, who preaches the Ethiopian Marxist party line, a young Ethiopian Jew proudly uncovers a battered Torah.

Because the film imparts so much information, and often drily, it does not even begin to develop a dramatic structure. At once thorough and concise, it simply presents the facts – the history and politics of an ancient culture that, through persecution, starvation, and assimilation, may disappear.