Response to Prof. Bauckham’s critique of The Lost Gospel

Click here to see part 2 of my response.

Assessing The Lost Gospel, part 1

Prof. Richard Bauckham from St. Andrews University has been posting scholarly reviews (so far, two parts) of the book I wrote with Prof. Barrie Wilson: The Lost Gospel: Decoding the Ancient Text that Reveals Jesus’ Marriage to Mary the Magdalene.

Prof. Bauckham agrees with our understanding of “Joseph and Aseneth” as a Christian manuscript. Where he seems to disagree is that it is a “coded history” of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. In the first part of his assessment of our book, he bases this disagreement on the following:

(1) The Title

“Joseph and Aseneth” appears in a compilation work by an unknown monk called by scholars “Pseudo-Zacharias”, i.e., not the real Zacharias. This monk gave his work a masterful title: “A Volume of Records of Events which have Shaped the World”. In this anthology, the monk included writings that he considered of world-shaking importance. Hence, it stands to reason that “Joseph and Aseneth” could not have been a simple story about an ancient Jewish patriarch, but an all-important Christian story that would qualify for a monk’s anthology of world-shaking events. This, obviously, is one argument in favor of the idea that “Joseph and Aseneth” is an encoded Gospel.

Prof. Bauckham wants to diminish the importance of the manuscript by arguing that the monk included works that were less than earth-shattering. To do this, he argues with our translation of the anthology’s title. It’s not an anthology of works that have “shaped” the world, he says. Rather it’s just an anthology of “Events which have Happened in the World”. This criticism is, to say the least, not very convincing. Nobody creates an anthology of books that record things “which have Happened” if he doesn’t think those things are important. By definition, all past events “have Happened”. But Pseudo-Zacharias does not include any grocery lists or laundry stubs in his anthology. He’s obviously more discerning, including in his anthology events such as the Emperor Constantine’s conversion and other such important things that “have Happened” and that are worthy of recording for a Christian. So if he preserves our text, there must be a Christian reason for it. Prof. Bauckham doesn’t offer any reason.

(2) The Contents of Book I

Prof. Bauckham’s second point is to go through the list of events that Pseudo-Zacharias records so as to try to find some less-than-earth-shattering events. He doesn’t do very well. One thing he points to is that Pseudo-Zacharias refers to the discovery of the relics of “Gamliel and his son Habib.” He does this in the same context that he refers to the relics of “Nicodemus and Stephen”. Somehow, because we refer to the latter but not to the former, we have done a great injustice to the context of our Gospel. Somehow, according to Prof. Bauckham, the reference to “Gamliel and his son Habib”, undermines our thesis. But it doesn’t. We point out that the relics of Nicodemus and Stephen are very important to our argument that the text is encoded. Nicodemus was a secret follower of Jesus and he survived, Stephen was an open follower of Jesus and he was killed. The moral being, “encode your beliefs”. We didn’t mention Gamliel, but we could have. Gamliel had a reputation among Christians of being a secret follower (Sabb. 116 a, b). So, again, Pseudo-Zacharias seems to reference secret teachings and codes.

Bauckham also points out that there’s another story we didn’t mention as forming part of the anthology. It’s a story concerning two Syriac Christian teachers named Isaac and Dodo. Again, though we didn’t get into this obscure story, it seems that these two teachers appeared “very acceptable” to the authorities while covertly teaching heretical ideas. In any event, the fact that their story is included in Pseudo-Zacharias does not prove that Pseudo-Zacharias recorded trivial matters. What it proves is that the other stories in the anthology should also be studied for the secret and heretical teachings they may be hiding.

When you read this part of Prof. Bauckham’s critique, you realize how strong our argument really is. If at the end of the day all you can say about the context that the book appears in, in its Syriac version, is that the title should be translated with a slightly different emphasis, and that two obscure teachers should also be included in the analysis, you realize that we’ve made a very strong argument indeed.

(3) A Monophysite Work

Prof. Bauckham now turns to the idea of “Monophysite Christianity”. Monophysites differed from Trinitarians in their idea of the nature of the Christ. Bauckham believes that Wilson and I underplayed the importance of Pseudo-Zacharias’ Monophysite beliefs. I’m not sure what this has to do with anything, except to argue that Monophysites had very specific theological issues and that a married Jesus was not one of them. Therefore, according to this thinking, Pseudo-Zacharias would never have included an encoded Gospel which disagreed with his Monophysite beliefs. According to this view, the Church’s overall persecution of all Christianities that diverged from its theology is irrelevant because not that much separated Monophysites from their Catholic brethren. If ever there was a roundabout way to criticize us, this must be it. The fact is that the Church burnt the Gospels that it didn’t like and the people who believed in them. In the 13th century, Cathars in southern France believed in a married Jesus. We don’t have Cathar documents because the Church burnt their scriptures and killed a million of their followers.

The whole point about the Church’s persecution is not to focus on one theological point between Monophysites and Catholics, it’s simply to explain that for hundreds of years before Pseudo-Zacharias created his anthology, some theological issues were debated in secret because you couldn’t debate them openly. This whole Monophysite digression is simply a way of blowing smoke – fancy smoke, but smoke nonetheless.

(4) The Letters about “Joseph and Aseneth”

Prof. Bauckham then addresses the two letters that are attached to the Syriac version of this text. We’re the first to get these letters translated into a modern language. They both talk about an “inner meaning” to the text. One of them explicitly says – by quoting Proverbs – that the text is dangerous, and that being open about it could get you killed: “The babbling mouth draws ruin near”, and “he who guards his mouth will preserve his life.” Sounds like life under Stalin. But Bauckham thinks that all this is meaningless. According to Bauckham, when it comes to “inner meanings”, all the writer means is that the text has a “Christian allegorical meaning”. Nothing dangerous there.

And when it comes to quoting Proverbs, according to Bauckham, the translator of the ancient text was extremely modest. When he talks about preserving one’s life, what he’s really talking about is that one shouldn’t be overly “confident in speaking”. Good grief.

(5) Censorship in the Manuscript

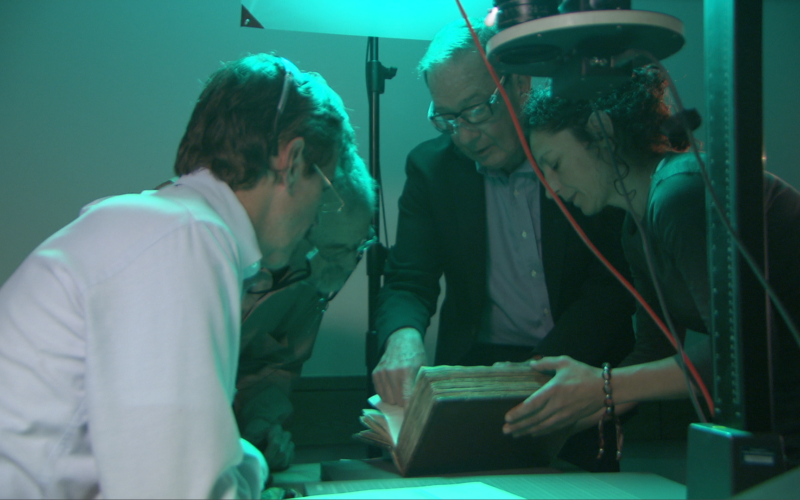

Prof. Bauckham then refers to the fact that the text is deliberately cut just as Moses of Ingila (the translator of the manuscript into Syriac from an ancient Greek version) is about to reveal its “inner meaning”. Basically, Bauckham believes that the text wasn’t purposely censored but was cut because of “carelessness rather than in a deliberate attempt to obscure.” He follows his visual analysis by saying that “I cannot really see how digital imaging would make any difference to this observation.” Well, Prof. Bauckham, it does. The fact is that you can see with the naked eye that the text has been deliberately cut with a sharp edge running right through the words. Furthermore, digital imaging, using multi-spectral photography, ruled out “carelessness” and confirmed that Moses’ letter was deliberately cut. Bauckham does concede that “one cannot say that Jacobovici and Wilson are wrong” about this point, but he believes that he’s created “considerable doubt”.

Part 1 of Bauckham’s critique is, in fact, no critique at all. It’s an attempt to create doubt by derailing the discussion into an examination of Monophysite Christianity, stating that the anthology is simply a collection of events that were not important but merely “happened”, and asking why we didn’t address the story of Isaac and Dodo. Prof. Bauckham ends the first part of his critique by taking issue with forensic photography, arguing that a deliberate cut is really a careless tear. I’ll go with the forensic photography.

In conclusion, the worst thing about Prof. Bauckham’s review is that it makes our book sound boring. It isn’t. It’s a story about first-century love, sex and politics and, incredibly, it’s about Jesus.