The Jesus Wife Papyrus: A reasoned argument from Hershel Shanks, editor of Biblical Archaeology Review

Article posted on biblicalarchaeology.org

Poor Karen King. The prestigious Harvard Theological Review (HTR) has withdrawn her article from its publication schedule—at least temporarily. It was supposed to go into the January 2013 issue. Not anymore! What did she do so wrong?

Poor Karen King. The prestigious Harvard Theological Review (HTR) has withdrawn her article from its publication schedule—at least temporarily. It was supposed to go into the January 2013 issue. Not anymore! What did she do so wrong?

Professor King is not some young scholar with a fresh Ph.D. At the Harvard Divinity School, she is the Hollis Professor of Divinity, the oldest endowed academic chair in the United States.

And of course everyone is talking about it. Google her name and (supposedly) more than 34 million entries are listed in less than a third of a second.

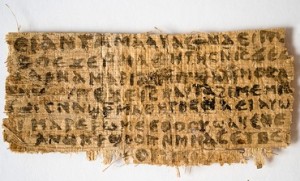

The article, as almost all of you know, is about an ancient Coptic papyrus text the size of a business card in which Jesus refers to “my wife.” (See “A ‘Gospel of Jesus’ Wife’ on a Coptic Papyrus.”)

King is an old hand at this kind of scholarly article. She has published lots of books and articles with this same scholarly heft. Her HTR article is long and heavily footnoted. It is cautious and restrained. And she has consulted a number of equally prestigious scholars to make sure her scholarship is sound. One, AnneMarie Luijendijk, a leading papyrologist from Princeton University, is listed as a contributor right under King’s name, almost as a co-author. Numerous other scholars are referred to in the article, including Roger Bagnell, director of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, to whom King refers as a “renowned papyrologist” and expresses her “sincere gratitude.”

So what did King do so wrong to deserve this?

Of course, the first thought is that she dared to suggest that Jesus was married—shades of Dan Bown’s fictitious novel The Da Vinci Code. But this is not true. King is explicit that this papyrus text has nothing to do with whether Jesus actually had a wife. This text, she says, “provides no reliable historical information” about “whether the historical Jesus had a wife.” And again: “[This text] does not, however, provide evidence that the historical Jesus was married” [emphasis in original]. King suggests the text dates from the fourth century and is a copy of a second-century document. “The importance of [this document] lies in supplying a new voice within the diverse chorus of early Christian traditions about Jesus that documents that some Christians depicted Jesus as married.” In other words, in the centuries after Jesus death, did some Christians think that Jesus had been married? That’s the thesis of King’s article.

There is no doubt that in the centuries after Jesus lived, Christians talked and wrote about the possibility that Jesus was married. This was part of Christian explorations of the meaning of sex and marriage. This discussion has been going on for a long time and numerous modern scholars have written about it. It includes the possibility, based on some apocryphal gospels, that some Christians in the centuries after Jesus lived thought that he was married to Mary Magdalene. In short, discussions like that in King’s HTR article are part of a vast scholarly literature.

Moreover, King is cautious even in her conclusion that some later Christians believed that Jesus was married. She finds the suggestion “plausible,” but this papyrus, she tells us, is “much too fragmentary to sustain these readings with certainty.” Elsewhere she repeats this hesitant conclusion: It is only “probably” the case that in the centuries after Jesus’ death, some Christians believed that he was married. In conclusion, King assesses this papyrus within the “rich literature that illustrates the enormous diversity of early Christian perspectives regarding matters of sex, gender, reproduction, and marriage … Already in the oldest extant literature, the letters of Paul, we hear of questions about whether to marry or engage even in marital relations (1 Corinthians 6–7).”

So why shouldn’t this scholarly discussion be printed in the Harvard Theological Review? Well, because the papyrus text might be a fake. Some clever forger may have been at work.

King thoroughly discusses this issue in her article. This is nothing she has tried to brush under the rug. Two anonymous reviewers raised questions about the authenticity of the text and suggested it be reviewed by experienced Coptic papyrologists. They had seen only low resolution photographs, but more importantly they were unaware that two leading Coptic papyrologists, Luijendijk and Bagnell, had already judged the text to be authentic.

It is no surprise that some scholars will view the papyrus and its contents differently. And this is the case here, particularly with regard to the authenticity of the text. This is certainly a legitimate question that should be discussed, along with all the other questions surrounding the text’s date and interpretation.

A number of scholars have discussed whether the text might be a forgery, but the only authority I know to declare it unqualifiedly “a fake” is Gian Maria Vian, the editor-in-chief of L’Observatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper. His unqualified conclusion is stated in an editorial in the newspaper; the Vatican is clearly concerned about King’s analysis of the text. With due respect for Mr. Vian’s scholarship, however, he is not well known for his competence in Coptic.

The chief academic to question the authenticity of the text is Francis Watson of Durham University in England. He is certainly skeptical, but that’s as far as he goes. He argues that the text “may be a modern fake.” His reason is that much of the text resembles the text of an apocryphal Coptic gospel, the Gospel of Thomas. Watson emphasizes that nothing in his analysis “make[s] it in any way certain that [this text] is a modern fake” [emphasis in original]. Other scholars, moreover, point out that such amalgams from contemporaneous texts are often found in authentic ancient compositions.

The bottom line is that there are a number of uncertainties about this text—its date, the text itself, its relationship to other texts of the period, and of course its authenticity. All these issues are—and should be—a matter of debate. At least two great Coptic scholars, Luijendijk of Princeton and Bagnell of NYU, regard the text as authentic, dating to the fourth century. So there are two sides (at least) to the authenticity debate.

What is wrong, however, is for the Harvard Theological Review to suspend publication because of the dispute about authenticity. Dispute is the life of scholarship. It is to be welcomed, not fled from. When a professor at the Harvard Divinity School, backed up by two experts from Princeton and NYU who declare the text to be authentic, presents the case—and tentatively at that—that should be enough for HTR to publish King’s article, not to cowardly suspend its decision to publish. Instead, HTR has cringed because there will now be a dispute as to authenticity. This is shameful.