What Wingate Wrought

Here’s an article about a military genius and great friend of Israel. You may not have heard of him. His name was “Orde Wingate”, a distant cousin of Lawrence of Arabia. As of today, I’m starting a new section “people you should know and probably never heard of”.

Here is an excerpt of an article by Max Boot on weeklystandard.com

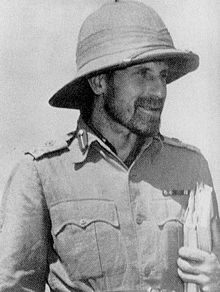

Everyone still remembers T. E. Lawrence, if only because of David Lean’s magnificent movieLawrence of Arabia and Lawrence’s own literary masterpiece,Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Yet far fewer remember Lawrence’s distant cousin, the British Army officer Orde Wingate, who was in many ways his World War II counterpart—not least in his eccentricity, his pungent writing style, his flair for publicity, and his tragic, premature death. A partial exception is to be found in Israel, where he is still remembered asHayedid (the Friend) for his Zionist sympathies. But Wingate remains little known in the United States or even in Burma, the land whose freedom he gave his life for. Last summer while visiting Myanmar, as the country is now known, I asked several well-educated Burmese if they were familiar with Wingate. I drew only blank stares. No doubt his name would draw equally blank looks from well-educated Americans, even those with an interest in military history.

That is a shame because Wingate was one of the most interesting, innovative, and influential, if also most aggravating and outrageous, commanders of World War II. He was one of the pioneers in Special Operations. Remember the way that a small number of Green Berets and CIA operatives, with links to indigenous allies and radios to call in airstrikes, helped to overthrow the Taliban in the fall of 2001? Wingate was one of the first to mount such “deep penetration” missions, in his case behind Japanese lines in Burma, Italian lines in Ethiopia, and Arab lines in Palestine. More broadly Wingate was an innovator who helped nascent Special Operations forces win recognition and resources despite skepticism about their utility among conventional soldiers.

Today Special Operations forces are not only an established part of the military; they are, in many ways, more prominent than their conventional brothers in arms. It was not always thus. Although there have always been daredevil soldiers and units sent on hazardous missions, formally organized Special Operations forces date back only to World War II. To come into being they had to overcome the antipathy of regular soldiers such as the British general who reportedly groused that they were “anti-social irresponsible individualists” who contributed “nothing to Allied victory” and “who sought a more personal satisfaction from the war than of standing their chance, like proper soldiers, of being bayoneted in a slit trench or burnt alive in a tank.”

Such skepticism was brushed aside in the dark days of 1940. When Winston Churchill took over as prime minister just as France was falling, he immediately established both the Army Commandos to “develop a reign of terror down the enemy coasts” and an entirely new civilian organization, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), to undertake “subversion and sabotage” in occupied lands—or, in his evocative phrase, to “set Europe ablaze.” So urgent was the situation that the formation of the commandos was approved three days after being proposed, and their first raid on the French coast took place 15 days later. Before long, numerous other British units were set up for operations behind enemy lines. The war in North Africa spawned the Long Range Desert Group, the Special Air Service (SAS), and Popski’s Private Army, all of which used trucks and jeeps to traverse trackless seas of sand, hitting the Germans and Italians where they least expected it. Not to be outdone, the Royal Marines, Royal Air Force, and Royal Navy formed commando-style detachments of their own. When the United States entered the war, it followed suit, forming the Army Rangers, the Marine Raiders, and other such units.

The volunteers—and generally only volunteers were taken—tended to be, in the words of the British Army captain W. E. D. Allen, either “the young and the keen” or the “stale and the restless”: “The efficient soldier, good at his job, generally ignored the notices.” Brigadier Dudley Clarke, who as a lieutenant colonel founded the British Commandos in 1940, wrote,

We looked for a dash of the Elizabethan pirate, the Chicago gangster, and the Frontier tribesman, allied to a professional efficiency and standard of discipline of the best Regular soldier. The Commando was to need something beyond the mass discipline which held the ranks steady when men stood side by side; his had to be a personal and an independent kind which would carry him through to the objective no matter what might happen to those upon his right and left.

This meant, he concluded, that the “men would have to learn for once to discard the ingrained ‘team-spirit’ ” of regular military formations.

For the full article click here.